Ease amounts in commercial patterns are one of the eternally frustrating problems of contemporary sewing. The amount of ease included in designs seems to vary wildly from pattern to pattern, even from the same company, so that the home sewer finds her or himself needing to sew a muslin/toile for each pattern. It adds yet another layer of complication to the puzzle that is pattern size selection. But where does the confusion come from, exactly? I’m thinking there are a few main culprits: patterns drafted with ease amounts that don’t fit the actual garment type, inaccurate pattern photographs, and lack of finished garment measurements to give an objective way to analyze final fit. (For simplicity’s sake, I’m only going to consider patterns for woven fabrics at the moment.)

What exactly is ease?

It’s the amount of extra space added to a pattern in excess of actual body measurements to allow for movement and style. Wearing or fitting ease refers to a necessary small amount of space included in slopers and almost every pattern type (with the exception of corsets, some foundation garments, and stretch fabric patterns) that allow the wearer to breathe, sit, bend, and reach in the garment. This is usually around 2″ of additional space at the bust, 1″ at the waist, and 1.5″ at the hip, no matter what the pattern size.

Design ease is a more variable amount of space added to patterns to create different style types, create silhouettes, and to give movement to the garment. Design ease amounts are proportional and depend to some extent on the size of the garment, though there are general industry standards for different fits that are the approximately the same from pattern company to pattern company.

Ease Standards for Different Garment Types

There are about five different categories of fit that pattern companies generally use to describe their patterns. Though there is a lot of variation from garment style to garment style, and the top of the pattern may have one fit and the bottom have another, this can be helpful in understanding how much ease to expect the garment to have. The McCall website here offers a chart of ease amounts for various fits. This chart doesn’t differentiate between design and wearing ease, so my assumption is that this is the total amount added to the body measurement.

Close Fitting (includes 0-2 7/8 inches of design ease at the bust)

Fitted (includes 3-4 inches of design ease at the bust)

Semi Fitted (includes 4 1/8-5 inches of design ease at the bust)

Loose Fitting (includes 5 1/8-8 inches of design ease at the bust)

Very Loose (over 8 inches of design ease at the bust)

Slightly more design ease is added for garments that are layered on top of other garments, such as jackets and coats. The design ease included at the waist and hip varies depending on whether the garment has a waistband or where the garment hangs from the body.

There’s a great piece that goes more in depth on the subject (here), though I’m unsure about the exact design ease amounts it lists. (That chart matches the McCall chart, which I think includes wearing ease and design ease in its amounts, so the amounts of *design* ease added to body measurements are probably smaller than it describes.) It has some very helpful visual guides to what different fit styles look like on the body.

Wearing and design ease standards seem formulaic enough that it’s odd there’s so much inconsistency. So many people on sewing forums and doing pattern reviews describe problems with way too much ease for their size. So where does the confusion come in? Do pattern companies not stick to their described standards? Does grading add excessive ease for certain sizes? I examined a set of patterns to see how this works out for a few different garment fit types from different eras (because I have strange ideas about what constitutes a good time) and found a few issues I’ll examine in detail.

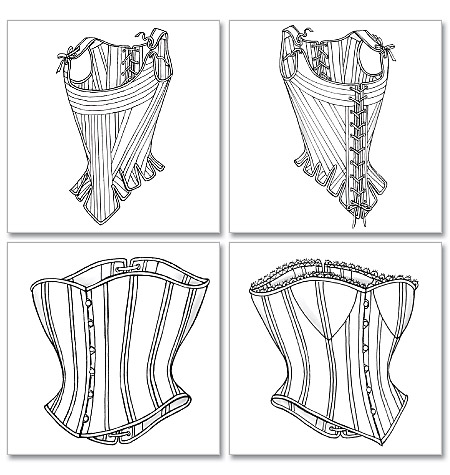

Grading Inconsistency and Wrong Ease Amounts for the Garment Type: Corset Patterns

Some of the problem may come from using the wrong pattern block or wrong design ease for the garment type, though this seems likely only for certain kinds of close-fitting garments like corsets and strapless bodices that require a very close fit to stay in place.

I looked at Butterick 4254 View C, sizes 12, 14, and 16, which is a historically based late 19th century style corset with a front busk and a laced up back. At the bustline, the finished garment measurements printed on the pattern match the body exactly at the bust. At the waist, for size 12, the pattern matches the body exactly. For sizes 14 and 16, the pattern is 1/2 inch smaller than the waist. So for this particular pattern, there are two fit problems. First, the ease seems to vary irregularly by size at the waist, which is problematic for predicting fit. Second, the lacing gap for most corsets is usually about 2″, so if we add that, the final corset is not going to fit as a sewist would expect it to fit. If the sewist is wanting a garment that fits something like a Victorian corset, they’re going to be disappointed, because there’s no way a period garment included 2″ of ease, and a corset would have nipped in at least an inch or two at the waist as well. Sewists using this pattern on various boards usually recommend sizing down about two sizes, sometimes more, in order to get the fit that one would want in a corset.

I also looked at Butterick 5797, View A, sizes 12, 14, and 16. It’s described as a corset, close fitting, and labeled with “Making History” (though, alas, there’s no info on the specifics of that history included). This one closes with a zipper in front and has no lacing. I found that based on the final garment sizes given, at the bust there is a consistent 2″ of ease for all sizes. At the waist, for size 12 and 14, there is 2 1/2″ of ease, and for size 16, there is 3″ of ease. At the high hip, there was approximately 1 1/2″ for all sizes. For this pattern as with the other corset pattern, it isn’t going to fit like an actual corset at all, so a sewist expecting that is going to be disappointed, though they might suspect that from the zipper. (Without lacing to allow movement with breathing, the zero ease typical of a corset isn’t really desirable or comfortable). An argument could be made for having more design ease at the waist for larger sizes since design ease is proportional, but if that were the case, the ease amount should increase between size 12 and 14 by some increment as well, but a corset is usually expected to nip in at the waistline.

What’s frustrating is that two “historical” corset patterns from the same company seem to vary in the amount of ease they use for similar garments in a way that is not transparent. Even if you give them the benefit of the doubt on 4254 and pretend that 2″ that should be indicated for the lacing gap are part of the pattern ease, when you compare the two patterns, the ease amount doesn’t change in the same way between sizes, so how can you predict the fit accurately? If you know the best size for you in one pattern, that same size may not work in the other pattern. Looking at the pattern envelope raises another issue as well.

Is Pattern Envelope Photography Realistic?

The photo on the envelope of Butterick 5797 seems to fit the model as a contemporary corset might, if worn without the intention to nip the waist. But if the model were wearing the size indicated for her on the size chart, it’s very unlikely it would fit this way. If a strapless boned bodice had 2″ of ease at the bust, it probably wouldn’t stay in place. If the model’s garment had 2 1/2″-3″ of ease at the waist, it probably wouldn’t appear this form flattering on her.

My suspicion is that models on pattern envelopes almost never wear the sizes of the garment they would be told to select on the pattern envelope, and during the photo shoot, clothing is probably pinned with clips to flatter body curves and hang just right. The photos of this particular pattern look lovely, but what’s the point of great product photos that don’t accurately depict the fit of the product? It creates an expectation that’s going to be disappointed.

Ease Amounts in Commercial Patterns over Various Eras

1930s

I was curious about ease amounts and silhouettes in other commercial patterns and over different eras, so I looked at several more examples of different garment styles for the sake of comparison.

The oldest pattern I looked at was a dress from 1934 from Mabs Weekly, one of the fashion magazines of the era that often included a free pattern. This one would have been a fitted bodice style. I don’t have the original illustration of the garment, but the pattern is for a 36” bust. The final garment measurements weren’t listed on the pattern, so I measured the pieces themselves and subtracted the seam allowances to find the finished measurements. The finished measurement of the garment at the bustline is 39.5″, for 3.5″ total ease.

1940s Lingerie Pattern Ease

I looked at another pattern, Advance 3067, for a slip from what I’d guess is the 40s from the envelope design and the lines. The slip doesn’t have a placket or closure and isn’t cut on the bias, so it’s close fitting but probably not as close to the body as some lingerie. (This image is borrowed from an Etsy listing here). I found that for a size listed as 32″ breast, the finished measurement (which I had to take from the pieces themselves) was 36″ after seam allowances were removed. At the waist, the garment had approximately 6.75″ of ease when darts and seam allowances were removed, which makes sense for a pullover style garment.

1950s Lingerie Pattern Ease

For this example, I examined a contemporary reissue of a 50’s era Simplicity bra pattern (Simplicity 4333). The contemporary version of the pattern is numbered 1426, and I looked at view C. *Represses rant about ugly contemporary pattern envelope design with all her might* But seriously, the 1980s wood stain exterior paint green of the Simplicity logo and the weird way the elements are balanced is just…no. NO.

There is some confusion with using the finished garment measurements in some reviews, as it’s unclear if the size represents the full bust. (My guess is probably yes, since that’s where the Simplicity site suggests measuring to select your pattern size. Personally, I think the high bust is the better starting point for accurate pattern selection, since it measures your frame rather than your breast fullness.) According to the size chart, the finished measurement matches the body measurement exactly at the bust.

Out of curiosity, I measured the pattern pieces for my likely size as well. For the size 12 pattern, the finished measurement is listed as 34″. But there is a button placket at the center back, and it’s unclear if those finished garment measurements include the amount that the band overlaps at the placket or not. I measured to the center line of that placket, essentially measuring the circumference of the garment when closed for wearing, and found that when seam allowances were removed, that size would actually be 33″, an inch smaller than the body, which isn’t going to be workable for a garment with no stretch. (Counting the overlap in the finished measurement would have given me a measurement of approximately 34 and 1/4″ full circumference.)

While there’s definitely some room for error on the part of my measuring, a lack of any ease for breathing and the lack of clarity in what the finished garment measurements actually mean are a problem. While the contemporary formulation of band size/cup size wasn’t being used in the ’50s, it seems odd to me that one of the Big 4 pattern companies couldn’t examine the pattern measurements and explain their sizing in a way that takes band size/cup size into account to better serve the needs of their current customers for the reissued version. If I could find the original pattern, I’d love to compare the ease standards and grading used in the original to the ones used in the reissue. I’m also curious how accurate the finished garment measurements printed on patterns usually are.

Contemporary Lingerie Pattern Ease

I looked at Vogue 8888 to get an idea of how much ease is used in contemporary lingerie pattern making as well. View A is a loose-fitting surplice robe. View C is a close fitting, bias cut pull over camisole. View F is a semi fitted pair of bias cut shorts.

What I found was that for the robe (View A), the bust included 6.5″ ease and the hip had 7.5″ of ease for all sizes. For the camisole, there was 3″ of ease at the bust for all sizes I checked, which might be just slightly above what the Big 4 ease charts describe as “close” fit by about 5/8″, but which makes sense given the lack of a closure and need to be able to pull it over the shoulders. For the shorts (View F), the hip had 3.5″ of ease. (I checked the actual pattern pieces for this view and found this measure to be accurate, too.) The waist had 8″ of ease, which, along with the stretch of the bias cut, would allow for them to be pulled over the hip without a placket or opening. These ease amounts aligned pretty accurately with the stated total ease amounts for the major pattern companies for different fits, and the ease amounts were the same for all sizes I looked at.

Contemporary Pattern Ease in Loose Fitting Garments

I looked at McCall 6649, a loose-fitting button up menswear style shirt in a B cup size, and found that the bust had 5 1/2″ of total ease, the waist had 6″ of total ease, and the hip had 6″ of total ease for all sizes I looked at (16, 18, and 20 for this pattern). So ease amounts were consistent, and matched the given ease chart amounts for a loose fit. I was curious, though, if the final garment actually fit as it’s depicted on the envelope or if it might be looser, especially at the waist. The model may be wearing a smaller size than the envelope would recommend for her body measurements, or it might be styled to be flattering, or maybe it’s just me.

I looked at one more “loose-fitting” pattern, the McCall 6465 loose tunic dress. For sizes 16, 18, and 20, ease amounts were consistent. It had 5.5″ of ease at the bust, 13.5″ of ease at the waist, and 8.5″ of ease at the hip. The ease amount at the waist seems large, but if the dress is pulled over either the shoulder or the hip, it would make sense for the narrowest part of the body to require more ease here. This one was a looser fit than the other pattern, so if a person was expecting “loose fit” to mean the same thing on both without pulling the patterns out to check the finished measurements, there might be some frustration with the results.

Conclusions

The patterns I looked at seemed mostly consistent with ease amounts described as “industry standard.” I can’t find much information on ease standards in ready to wear, so I’m curious how those industry standards are applied outside of patternmaking for home sewing.

If ease amounts in patterns are relatively standard, then where does the confusion and frustration come in? I’m thinking some of it is the stylized photography of pattern envelope photos. When we see a photo of a finished garment, there is a certain automatic assumption that the photo is more realistic than the highly stylized, exaggerated silhouettes of vintage pattern envelope fashion illustration. But the photos aren’t as realistic as they seem if the samples are potentially being selected to flatter the model and the garment rather than depicting the actual fit of the pattern if it were sewn to the model’s body size. This is compounded by the possibility that clothes are pinned in place or pinned closer to the body and that photo editing might be creating the illusion of closer waistlines or trimmer leg silhouettes than the garment really gives.

So what’s a sewist to do to avoid pulling her/his hair out? The best indicator of final fit is the finished garment measurements. You can check the total ease amount by subtracting actual body measurements on the measurement chart from the finished garment measurements printed on the tissue, if they’re present. If not, it’s worthwhile to measure the pieces at least at the bustline to get an idea of whether the fit the pattern is said to be is the fit you’re expecting, and the waist and hip measurements are helpful as well. If you have a sloper that you work with for pattern fitting, you can rotate the darts to the approximate position of the sewing pattern you’re comparing it to to see how much the additional space the sewing pattern has, and whether this works for you for the fit you’re seeking.

Finally, it’s a good idea to know what kind of ease you prefer in your garments, and a great way to do this is to measure ready to wear clothing you already have that fits the way you’re wanting your sewn garment to fit. For example, if you have a skirt that is just long enough and has the amount of ease you want in a close fit, measure its actual dimensions and compare with your body measurements to get an idea of what desirable fit is for you. I’m incredibly picky about how pants fit, so as soon as my pregnancy belly resumes a more semi-permanent, somewhat back to normal state, I will be measuring a few of my favorite pairs of jeans for exact inseam length, favorite boot cut flare amount, and crotch depth that is tight enough to give some curvy definition to my back end without being pinchy or uncomfortable. In my own patternmaking future, I hope to help with the ease confusion issue by listing final garment measurements clearly and offering consistent descriptions of fit or an explanation of the amount of ease so that, hopefully, the sewist can know what they are getting into without having to sew muslins of every pattern.

If you have frustrations with pattern fitting because of excess ease, I hope that this was helpful. Do you have any tips or strategies that help you to get consistent fitting results from commercial patterns? I’d love to hear them!